- Home

- Jean Stone

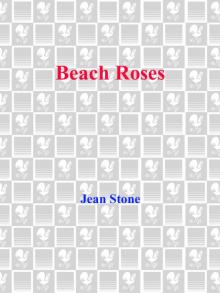

Beach Roses Page 24

Beach Roses Read online

Page 24

Ginny took off her bandana and ran her hand through her short, dark hair. “That explains it.”

“Explains what?”

“He wanted to know where Jackie Kennedy lived, where Carly Simon lives, and where John Belushi’s buried.”

“Shit. What did you tell him?”

Ginny smiled. “I gave him directions to the cemetery in Chilmark.”

They had a good laugh over that one, and Rita finally knew what she needed to do next.

When Faye returned from breakfast and from Hannah’s, she found Greg in the backyard, sitting on one of the Adirondack chairs that faced the water. She told him about R.J. and about Hannah’s daughter and that R.J. had agreed to look for her.

Greg had smiled, then said, “Good. Now sit down.”

She sat. “We’re going to get dirty,” she said, lightly brushing the broad arm of the chair. “I haven’t called the cleaning people or the lawn service, to get ready for the season.”

A moment passed before Greg said, “I used to love to come here the first weekend of every year, when there was so much activity all around—vacuum cleaners vacuuming, mowers mowing, the smell of disinfectant in the kitchen and the bathrooms—as if the world’s filthiest people had stayed here over the winter and we had to rid the place of every germ and dust bunny or perish from the earth.”

Faye smiled.

“Dana and I hid under the porch and pretended we lived underground. We brought Geraldo with us and tried to train him to be our lookout for the big, bad adults out in the world.”

Geraldo had been Mouser’s predecessor, a fluffy black cat that hated being outdoors, that chose Dana’s bed as his place, no matter where the family was. “And was he a good lookout?”

“No. He kept running away.”

Faye looked off toward the water. It had been a long, long time since she’d thought of Dana without pain; it had been a long, long time since she’d talked about her with another person who had memories of her, too.

“Whenever I’ve thought of you over the years,” Greg said, “I’ve always pictured you here. I never saw you in the house in Boston, just here, on the Vineyard, where we always were so happy.”

“Were we, Greg? Were we happy?”

His blue eyes narrowed in thought. “About as happy as any family can expect to be, I guess. Not as much as some. More than many.”

He was right. They had been happy. One season they’d been hooked on playing checkers, another with making jigsaw puzzles. One summer they’d found so much wampum they made “authentic” jewelry, including the pinkie ring Dana had given Claire.

Playing games, hunting wampum, making jewelry: They’d done these things as a family—Greg and Dana, Faye and even Joe.

Faye had assumed that the joy would last forever.

“I knew when Dana started drinking,” she said. “I think I knew it from the first night she came home drunk. She was only fifteen, wasn’t she?”

Greg’s gaze grew distant, melancholy. “Yeah,” he said, “I guess.”

“I told myself she was going through a teenage phase. I told myself that it would pass.”

“It didn’t pass.”

“I know.”

Greg folded his hands. “Sometimes it was my fault. I drove her places, and she’d find a way to drink. She made me promise not to tell you and Dad. She threatened that if I did, she’d tell you I was gay.”

Faye nodded. She understood.

He laughed. “Dana would do anything if it meant getting her own way. Most times it was easier to agree than to try to change her mind. I wish it hadn’t been like that.”

Faye shook her head. “Your sister was a charmer,” she said. “She was pretty and smart, and maybe she had too much going for her. She was a lot like your father. Yes,” she nodded, “she was a charmer.”

A tiny smile curved at the corner of Greg’s mouth. “Sometimes I wonder what she would have become. What kind of woman, what kind of person.”

A long time ago, Faye had wondered those things, too. In recent years she’d labeled those thoughts too painful and urged them from her mind. “We’ll never know, Greg. We’ll never know a lot of things.”

They sat quietly once again, the sound of hungry seagulls circling the sky.

“You’re not really going to sell this place, are you, Mom?”

“That depends on you.”

“Me?”

“Do you want it?”

“I live in Arizona.”

“Right now you do. But what about later, down the road? After I’m gone?”

Greg laughed. “Geez, Mom. Don’t talk like that.”

She reached across the small V that separated their Adirondack chairs. She took his hand in hers. She summoned all her strength. Then she looked into his eyes and said, “Greg, I had breast cancer again this winter. I think this time I’m going to die.”

“Hey, asshole, he’s not there,” Rita said, stepping from behind a tree in Chilmark Cemetery. She’d waited for an hour and had nearly given up, thought that he’d come and gone or decided not to come at all.

The man angled his camera and clicked the shutter.

She moved a little closer. “I said, he isn’t there. It’s only a grave marker that says ‘John Belushi.’ Everyone knows they moved his body on account of tourists. On account of parasitic, sensationalistic scum like you.”

He turned the camera toward her. The shutter clicked again. Rita held her hand up to her face. “You’re such a jerk,” she said. “How much do you get paid to do this shit? To trample other people’s lives with your first amendment bullshit?” She reached out and grabbed the camera. She fumbled with the back, trying to get the film.

The asshole laughed. “Nice try,” he said, “but no film. It’s digital. And by the way, if you’re looking for the shots of Katie, I e-mailed them last night.”

She dropped the camera. “You bastard.”

He laughed again.

“Who do you work for?” she asked.

“Wouldn’t you love to know.”

“I’ll pay you.”

“Not enough.”

“You don’t know that.”

“Yes I do.” He smirked and bent down to retrieve the camera.

It was all Rita could do to stop herself from planting her sneaker on his face. Instead, she stomped off across the tombstone-sprinkled lawn, reminding herself that at least she had the phone number he’d called not once, but seven times. Maybe when she and Katie learned what rag it was connected to, she’d call that cop in Brooklyn who’d tracked down Ina’s funeral. For a little more penuche, he might be willing to pay the tabloid a visit.

They’d spent the rest of the day on the beach, searching for wampum, in honor of Dana. They hadn’t found any. After Faye had told Greg about the breast cancer, Greg wanted to call Joe: Faye said please don’t, that she had made peace with Joe and that was how it should be.

“Isn’t there anything the doctors can do?” Greg had asked after they’d moved from the yard to the sand.

Faye had smiled and held his hand. “It’s okay, honey. If I die, at least Dana is there.”

But early that evening, as she stood before the full-length mirror in the hall, Faye wondered why she hadn’t gone for her last mammogram. Had she been so resigned to die, that she no longer cared?

But Greg was in her life again.

A small twinge fluttered in her heart; she made it go away.

She clasped the silver choker at her throat and examined the way the pewter-colored trousers fell around her legs. They were too big. She had refused to weigh herself; she refused to live with the dread of wondering if she’d wake up in the morning or if she had lost weight or if she’d be tired that day.

Maybe the weight loss was from the cancer, or maybe it was from the fact that she’d been so busy. It certainly wasn’t from worry, because Faye knew she’d reached acceptance when she’d been faced with that word “recurrence.”

She turned back to her

outfit, to her evening, because all she could do well now was live in the moment, that moment, right now.

She closed her eyes and made herself focus on the hope that her pretty, short-sleeved cashmere sweater would compensate for the baggy pants.

“My beautiful mother,” Greg said as he stepped up behind her. “You have always been so beautiful, even if you’ve been sick.”

She opened her eyes and turned to kiss his cheek. “You don’t mind that I’m going out tonight?”

“No. I’m glad you have a date. As long as you’re home by midnight.”

Faye laughed. “I don’t think that’s a problem. The Vineyard still has no nightlife except in July or August.” She brushed the front of her trousers. “Do these look okay? They’re not too loose?”

“You’re wonderful. And this guy is very lucky that he found you.”

She laughed again, and around those edges of acceptance, joy slowly crept in. Then she felt another twinge, a warning that this would end too soon. She cleared her throat. “R.J. is lucky, all right. He’s lucky he found you. Otherwise he’d be dining alone tonight at the hot dog stand in Oak Bluffs.”

“Mom?” Greg asked, as Faye went into her bedroom and began to switch her things from her black purse to her gray. “What about Hannah’s daughter? Do you think he’ll find her, too?”

“I don’t know,” she said. “He confided to me that it won’t be very easy; not like with you. Chances are her Social Security number won’t have showed up yet at the Internal Revenue Service.”

“That’s how he found me? Because I pay my taxes?”

Faye smiled and held her palms up to his cheeks. It was so hard not to keep touching his face, his hands, his hair, anything to reassure herself that he was really there. “I didn’t ask him for specifics. I only cared that you were found.”

“But this girl,” he said. “She’s fourteen.”

“She’ll be fifteen this summer.” Neither of them had to mention that Dana was fifteen when she had begun her dance with death.

“I’ve made a decision,” Greg said suddenly, or at least it seemed suddenly because Faye did not realize he’d had decision-making on his mind. “I’m staying here with you.”

She stopped and stared into his bright blue eyes. “You live in Arizona,” she said. “I said I’d sell this place and move out there …”

He shook his head. “You don’t belong in the desert, Mom. You belong right here. And I belong here with you until, well …”

“But your business …”

“Mike can handle it. We’re coming into summer. Not exactly tourist season when the temperatures shoot past a hundred.”

“But what about your father?”

“He’ll be fine, Mom.”

They looked at each other. Greg’s eyes were the first to fill with tears. “Please, Mom. Let me stay home with you.”

She hugged him once again and said it would be all right, at least for the summer, and then, downstairs, the doorbell rang.

TWENTY-SEVEN

“Take down the billboard,” Katie said into the phone with more conviction than she’d felt since her decision to have her baby and delay the radiation. She glanced from the phone to her mother, then to Rita, who had wasted her whole day on Katie’s behalf, searching for a man and the source of a phone number. Katie could have saved her friend the trouble. She turned back to the phone. “I don’t care if you have to crawl up there on your hands and knees and dismantle it bulb by bulb. Take down the billboard, Daddy. I will not do Central Park.”

“It sounds like Joleen’s been putting ideas in your head,” Cliff responded on the other end of the line.

“This is my choice. Once my baby is born, I’m going to have a real life. I don’t even know if I’ll want to sing again.”

“You’ll sing again. It’s in your soul.”

She closed her eyes as if to block the thought. It was the first time she’d called her father since the funeral, the first time she felt strong enough to withstand his manipulation.

Manipulation.

Until now, it had worked every time.

Your mother left us, Katie-Kate.

I’ll never leave you, Katie-Kate.

I’ll help you own the world.

She had never been sure if she’d wanted to own the world. But it was what he’d wanted for her, or maybe for him, in addition to the money and the fame that her cloned image of Joleen had wrought.

“I can’t cancel the date, honey.” His voice had dropped now; it was serene and almost sorrowful. “It would cost me a small fortune. You canceled the tour. You canceled the CD. Your old Dad’s not in the most solvent state.”

Katie squeezed her eyes shut. “That’s a lie. Joleen has more money than she knows what to do with. I suspect we do, too. I figure you make me keep working because you don’t know what else to do since you screwed up our family and your life.”

Cliff didn’t deny it.

“Cancel the fucking concert, Dad. Or I’ll tell the world my father sunk so low he actually paid someone to take my picture and sell it to the tabloids.”

The loud silence that followed, sadly confirmed Katie’s suspicions. She looked back to Rita, who still held the paper with the New York City phone number.

“I didn’t do it for the money, Katie-Kate. I did it for you. You’ve been out of the spotlight too long. People might think you’re like your mother …” He sounded so pathetic, Katie couldn’t listen.

“I’m not my mother,” she seethed. “For once in your life, stop trying to turn me into Joleen. I am your daughter and I’m having a baby and I have breast cancer and I am not Joleen. For godssake, Daddy, cancel the concert and stop that awful man from printing that picture.” She snatched the paper from Rita. She looked down again at the phone number that the man named Darryl Hogan had called seven times from Mayfield House, the number that did not connect to a newspaper office as Rita had thought, but to a phone in Cliff’s penthouse overlooking Central Park.

“No,” Cliff replied. “I can’t stop the picture and I won’t cancel the Park.”

They ate dinner at Lambert’s Cove as two adults might do, trading conversation about art and poetry and allegories from the Bible that might or might not be true. Faye had forgotten that R.J. had been a minister; she had not, however, forgotten that he was a man.

And when the meal was over and they’d had coffee and Kahlua, it seemed the most natural thing in all the world to go to his room at Mayfield House.

“If you say no, I’ll understand,” he said.

“I won’t say no,” she answered.

And before Faye realized what was happening, she was floating up the stairs of the gracious Captain’s house and entering a room that was decked in chintz and had a high, four-poster bed and a tall, manteled fireplace where R.J. built a fire.

She knew what he was planning and she prayed he would not stop.

He pulled the comforter off the bed and dragged it to the floor in front of the warmth. “Come here,” he said, and so she did.

“I have to tell you something.” She looked into the flicker of the newly sparking flames. It was less stressful to look there than into his eyes.

He leaned too close to her; he began to slowly unbutton the buttons of her sweater. She knew that she must stop him before he reached the part that uncovered her tattoo, her stamp that said cancer had been there and, she supposed, still was; she must stop him before he reached the other side and the implant that wasn’t really her.

“I know about your breast cancer,” he said, lowering his face to kiss her throat. “I know about the first one and I know about the second. I know everything. I’m a detective, remember?”

Then, when her sweater was fully open and her bra unfastened, he kissed her gently all over before removing her pants that were too big, and they made love into the night.

“Make a fist,” the lab technician said as she tied the tourniquet around Hannah’s arm.

Hannah made a

fist and closed her eyes: just because she’d been in medical school didn’t mean she liked having tests done on her. She closed her eyes, though, purely out of habit, for she was far too preoccupied to care that the deep prick into her arm would suck the life’s blood out of her.

After all, what difference would it make?

If she survived breast cancer, surely she would not survive Riley’s having run away.

The needle plunged into her arm, then slowly drew out her blood. She ignored the lightness in her head and thought about her daughter, as she thought about her every minute of her days and nights.

Where was she?

Was she cold and scared and hungry?

Or was she on a bus to San Antonio, high on her adventure, feeling the rush of escape that Hannah remembered feeling so long ago?

It would be easier to let the cancer have its way and take Hannah from this pain. The school could find another science teacher easily enough. And Evan could pull himself together like he’d done before. He could find another, better mother for Casey and Denise, someone without murder in her past; someone who was a better mother than one who could cause a child to run away.

“Okay, Mrs. Jackson,” the technician said. “Keep your arm up for a minute.”

Mrs. Jackson? Most folks were on a first-name basis on the Vineyard, no matter what the age. Only students called teachers “Mr.” or “Mrs.” Hannah tried to place the girl in the white lab coat. “Do I know you?”

The girl smiled. “Eighth grade, class of ‘91. Your science class is what got me interested in biology. And phlebotomy.”

Oh, God, Hannah thought. Sometime in the last few years she’d become so old that her former students were now her caregivers. A small eddy of bile pooled in her throat.

The girl looked at Hannah’s paperwork. “Next stop, chest X ray. Then you’re finished for today.”

At least her former student didn’t say that the tests were the first of several precursors to the mastectomy. Perhaps losing a breast was as insignificant to the class of ’91 as it now was to Hannah.

How could death be so imminent when Faye felt so alive?

A Vineyard Morning

A Vineyard Morning A Vineyard Summer

A Vineyard Summer A Vineyard Crossing

A Vineyard Crossing A Vineyard Christmas

A Vineyard Christmas Beach Roses

Beach Roses Off Season

Off Season Birthday Girls

Birthday Girls Once Upon a Bride

Once Upon a Bride Places by the Sea

Places by the Sea Trust Fund Babies

Trust Fund Babies The Summer House

The Summer House Tides of the Heart

Tides of the Heart Sins of Innocence

Sins of Innocence Four Steps to the Altar

Four Steps to the Altar Twice Upon a Wedding

Twice Upon a Wedding Three Times a Charm

Three Times a Charm